Yesterday I noted that David Cunliffe’s recent speech on the economy contained very little beyond populist twaddle aimed at painting himself as the champion of the ignorant and defender of the bewildered. I did not, however, devote much energy to pointing out specifically where and how Cunliffe was wrong.

Cunliffe seeks to exploit the credulity of those who haven’t the foggiest notion of how an economy actually functions – those dissatisfied by the Labour Party’s refusal to once again advocate for a command economy. And to fuel their fervour, Cunliffe threw his listeners plenty of juicy post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacies and more than a few straight out factual errors in support of their shared delusion that economic freedom has been bad for the economy.

But if Cunliffe’s case against the economic reforms of Roger Douglas in New Zealand, Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US is weak, is there a stronger case to be made for economic freedom?

Cunliffe’s central argument is that the world began moving away from interventionism in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Three decades later, the world economy is flat following a recession caused by a financial crisis that began in the property markets. Therefore, so the argument runs, free markets do not work. Cunliffe also states that austerity prolonged the Great Depression.

With respect to the claim that austerity measures prolonged the Great Depression, it should be noted that the depression was greatest in those countries that did not respond to the crisis by cutting government spending. In the US, Hoover responded to the economic downturn by:

- almost doubling federal spending from 1929 to 1933

- expanding public works projects to create jobs

- pressuring businesses not to cut wages, even in the face of deflation

- increasing trade barriers

- implementing the largest peacetime tax increase in American history

Hardly austere, surely. Unemployment in the US peaked in 1933 at about 25%, before declining to around 14% by 1937.

In Britain and Australia, where the governments responded by cutting spending and balancing budgets, unemployment rates peaked sooner at a lower level, declined faster and were below 11% in both countries by 1937.

Admittedly, correlation is not causation. Britain and Australia may have recovered faster had they implemented a stimulus, and perhaps the depression would have been deeper in the US had they not. But the data don’t support Cunliffe’s argument.

As for the resurgence of liberal economic policy following the post-war infatuation with Keynes, because economies are influenced by more than the economic policies of the government in power, one cannot simply look at economic performance before and after the implementation of a policy or a suite of policies and draw firm conclusions. However, by comparing the relative performance of several economies stronger inferences can be drawn about what effect policy settings are having.

Scott Sumner of The Money Illusion had a go at this here in 2008. Here’s his data:

| Country |

1980 |

1994 |

2008 |

| United States |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Argentina |

0.395 |

0.300 |

0.309 |

| Australia |

0.841 |

0.770 |

0.837 |

| Britain |

0.688 |

0.705 |

0.765 |

| Canada |

0.905 |

0.818 |

0.843 |

| Chile |

0.210 |

0.251 |

0.311 |

| France |

0.780 |

0.730 |

0.713 |

| Germany |

0.803 |

0.812 |

0.763 |

| Hong Kong |

0.547 |

0.845 |

0.948 |

| Italy |

0.756 |

0.754 |

0.675 |

| Japan |

0.732 |

0.815 |

0.736 |

| Singapore |

0.577 |

0.899 |

1.064 |

| Sweden |

0.868 |

0.777 |

0.794 |

| Switzerland |

1.146 |

0.987 |

0.915 |

The above data, from sourced from the World Bank, show per capita income in terms of purchasing power parity expressed as a ratio of US per capita income. Countries such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Chile and the UK whose economies were heavily liberalised have become wealthier relative to the US. European countries who embraced economic reform less wholeheartedly have performed less well than the US. Australia declined in the 80s, but gained ground after it began its economic reforms in the 1990s.

Over the last three decades, the period Cunliffe refers to as a “mostly unmitigated disaster”, countries with free economies have performed well relative to more statist economies. The picture for the European countries would surely be worse had they not, during the same period, been transforming their continent into a large free trade zone.

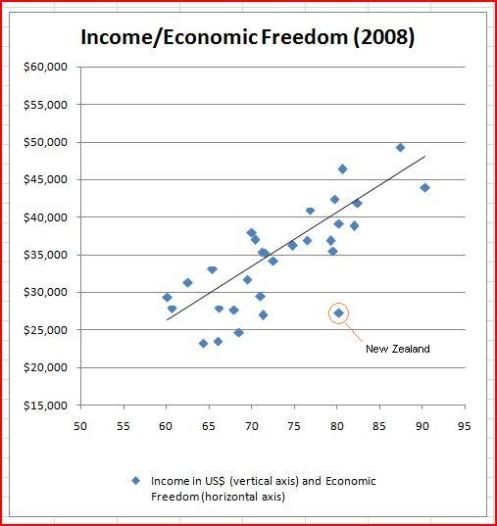

This graph, also from Sumner (except for the label on New Zealand, which is all my own work), tells us much the same thing.

Economic freedom, the bogey-man of David Cunliffe’s version of history, correlates very strongly with wealth. What’s most interesting about this graph, however, is the extent to which New Zealand is an outlier. All else being equal, New Zealand’s level of economic freedom in 2008 should have seen us around US$10,000 per year better off.

Sumner identifies two likely reasons for this. The first being our geographic isolation, and the second being that our comparative advantage is in agriculture, which is still highly protected in many large economies. Both of these explanations seem highly plausible.

Any government elected on the back of Cunliffe’s rhetoric would take New Zealand in completely the wrong direction. Isolation would still be a problem, but New Zealand would become a steadily less attractive place to invest and do business. Rather than seeking to turn back the clock and to return New Zealand to the days of wage orders and price freezes, a credible economic plan should seek to put New Zealand at number one on the economic freedom rankings.